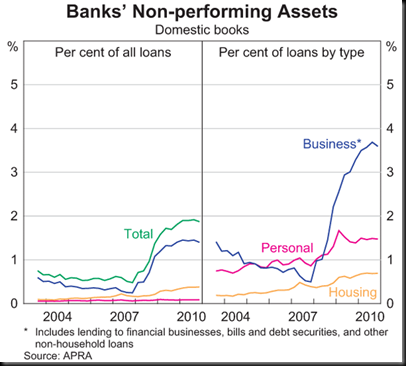

The latest (March 2011) RBA Financial Stability Review includes the following chart showing default rates amongst different classes of bank assets:

This was discussed in some detail over at Business Spectator.

I’d be very interested to get a better handle on what constitutes “non-performing”. The Housing data used here obviously reflects 90 day arrears – its broadly consistent with the 90 day numbers reported by Fitch, S&P and Westpac. However, I’m not sure what the Business and Personal default rates reflect – my suspicion is that they are simply a reflection of absolute actual default levels, irrespective of the term or severity of the defaults. If this in fact the case, I’d have a few issues with the analysis:

- I don’t really understand why 90 day home loan arrears are treated as non-performing but 30 days aren’t. A loan that’s 30 days overdue can hardly be called “performing”, given that they’ve probably missed two fortnightly payments by that stage

- Bear in mind that almost all Australian banks measure their home loan arrears on a “scheduled balance” basis, not a “missed repayments”. This means that the arrears balance is only 30 days overdue if the current balance exceeds what the balance should have been (if all payments had been met) by the amount of a month’s payments. If the borrowers had been making extra voluntary payments when the going was good (and huge numbers of people do), they could go for months without making a payment before their current loan balance exceeds the scheduled balance. On the other hand, if the “missed repayments” method is used, the earlier voluntary payments don’t count and the 30 day arrears position is reached as soon as a month’s worth of repayments are missed.

S&P’s regular RMBS Performance Watch documents these different approaches to default measurement. I’m assuming that the RBA/APRA data reflects the same approach as the S&P data, although I couldn’t find anything to verify if that’s the case. If it is in fact the case, the “housing” line in the graph above could conceivable be well above 2%, if 30 day arrears and missed repayments were used.